The Well-being of undergraduate medical students in COVID-19 pandemic; mixed method design

Introduction and Aim: The COVID-19 pandemic had many effects on the undergraduate medical education. The aim of our study was to determine the well-being of undergraduate medical students during pandemic, and to make future implications for institutions to support their medical students’ well-being.

Methods: This is a mixed-method study. The population of the research consists of from 1st to 5th year medical students. The research process was carried out in 3 steps, which are respectively: ‘focus group interviews’ via Zoom with a group of 6-8 volunteer students from each year; the formation of ‘Student Information Form’ based on content analysis of focus group interviews; online application of ‘Student Information Form (SIF)’ and ‘Wellness Star Scale (WSS)’ to volunteer students.

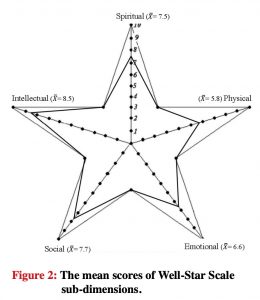

Results: The mean scores of the WSS sub-dimensions were: Intellectual = 8.5 (¯X_ND); Spiritual = 7.5 (¯X_ND); Physical = 5.8 (¯X_ND); Social = 7.7 (¯X_ND); Emotional = 6.6 (¯X_ND). A significant difference in favor of positive emotions was observed between the well-being spiritual score average of the students in the negative emotions group and the positive emotions group [p < 0.05]. A significant difference was found in favor of men between the female and male students’ well-being intellectual point average [p < 0.05]. The themes of emotions, learning process, well-being, difficulties and problems, achievements, coping methods, career planning, and suggestions emerged from qualitative data.

Conclusion: Among the ways of coping with the pandemic, healthy lifestyle behaviors such as nutrition and physical activity seem to come to the fore. Among the difficulties brought by the pandemic, “health concerns” were more due to the ignorance/inadequacy of preventive and therapeutic health services, especially in the early stages of the pandemic, and continued due to uncertainties after vaccination. Medical faculties should offer solutions that will ensure the continuity of social interaction and the preservation of the learning climate, which is interrupted in pandemic and similar situations.

Full Article

Introduction

Well-being has become a concept handled in designing health policies and focused on developing strategies to improve health status in recent years.(1) Well-being was explained as “a way of life oriented towards optimal health, in which body, mind, and spirit combine for an individual to live fully and functionally in his/her social and natural environment.”(2) Well-being is a concept directly affected by the physical and social environment in which the individual lives, such as happiness, functionality, quality of life, and life satisfaction. Various models have been established that provide guidance in showing which areas of life should be considered in assessing well-being.(3,4) The Well-Star Model (WSM), developed by Korkut-Owen et al. evaluates well-being with the following five sub-dimensions: emotional well-being; spiritual well-being; intellectual well-being; social well-being; and physical well-being.(3-5)

Despite all these definitions, it is a fact that there is conceptual confusion regarding the connection of well-being with the concepts of health. Health is defined as a concept that includes social, cognitive, emotional, spiritual, and physical elements, while well-being is explained as the integration of these elements, and high well-being is the balance of these elements.(6) The COVID-19 pandemic has serious effects in many areas of life in the world and our country. As of November 23, 2021, deaths due to COVID-19 in the world have reached 5, 158, 211.(7) Social restrictions due to the pandemic have led to the restrictions in transportation, arts and sports activities, the suspension of education, or the transition to distance education, the closure of restaurants and places of worship in many parts of the world, resulting in disruptions in social interaction in many aspects.(8-11)

The COVID-19 pandemic inevitably has serious effects on medical education in Turkey as well. Particularly, interventional skills and on-the-job training activities cannot be performed, group work and clinical practices as a team were interrupted, and most of the training is given in the form of distance theoretical lectures.(12,13) The aim of our study was to determine the well-being of undergraduate medical students during pandemic, and to make future implications for institutions to support their medical students’ well-being. The main research question that we seek the answer was: “How has the well-being of medical students been affected during the COVID-19 pandemic?”

Methods

This is a mixed method design study, including quantitative and qualitative research methods. The sample of this research consists of 1212 students from 1st to 5th years studying in Karadeniz Technical University Faculty of Medicine. G*Power 3.1.9.7 package program was used for sample size. The sample sizes required for the t-test and variance analyses in the study were calculated. In order to obtain statistically significant results in this study, the effect size is considered to be medium, the probability of error is 0.05 and the statistical power is at least 0.80, at least 200 students was needed.(14) The convenience sampling method was used to determine sample of study. All volunteer students who were registered students of the faculty at the time of the form and scale application and had no barriers to filling out the online questionnaires were included in the study.

Data Collection Tools

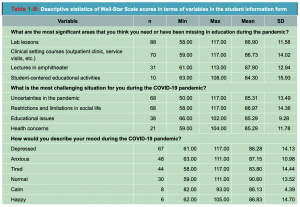

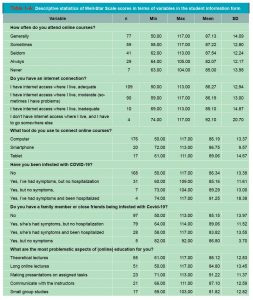

The quantitative data on the well-being of undergraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic were collected with the “Student Information Form (SIF) the “Well-Star Scale (WSS)”, and the “Semi-structured Focus Group Interview Form”. The SIF was developed by the researchers. SIF consists of 14 items regarding online education and personal information in the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1).

The WSS is a 5-point Likert-type scale with 24 items created by Korkut-Owen et al.(5) The scale is scored between 1 (doesn’t reflect me at all) and 5 (completely reflects me), with a minimum of 24 points and a maximum of 120 points. High scores indicate the high well-being status of the respondents. The WSS consists of five sub-dimensions: spiritual (7 items), intellectual (4 items), emotional (5 items), physical (4 items), and social (4 items). The Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient of the WSS was found to be 0.84, and 0.83, 0.72, 0.60, 0.57, and 0.65 for spirituel, intellectual, emotional, physical, and social sub-dimensions, respectively. Based on the data, since the Cronbach alpha, internal consistency coefficient is 0.90, the reliability of the scale is considered sufficient. The Semi-Structured Focus Group Interview Form including 11 questions related to the sub-headings of ‘emotional well-being’, ‘spiritual well-being’, ‘intellectual well-being’, ‘social well-being’, and ‘physical well-being’ was created by the researchers (supplementary material 1).

Research Process

1. Step: The SIF and the WSS were applied to 213 volunteer students selected by convenience sampling method from different years via the Google Questionnaire application.

2. Step: For the focus group interviews, 6-8 volunteer students who approved the interview recording were determined by the purposeful stratified sampling method for each year. Interviews were held on different dates in May 2021. The researchers used the “Semi-structured Focus Group Interview Question Form”. Focus group interviews were conducted on Zoom, in an average of 60 minutes, and the interviews were recorded.

Analysis of Quantitative Data

Descriptive statistics of the variables in the Student Information Form were calculated in terms of the scores on the WSS. T-test and analysis of variance were used to test the significance of the differences between the mean scores of the WSS in terms of some variables in the student information form. The normality assumption required for these analyzes was provided by both kurtosis-skewness coefficients and normality tests (Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk).(15-16) Analyzes were carried out with the SPSS 25 program.

Analysis of Qualitative Data

Content analyzes of the focus group interviews were made by two researchers (SA and BT). The steps followed in the analysis are illustrated in Figure 1. This study was approved by Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research Ethics Committee. (Number: 2021/7, date: 24.02.2021).

Results

Quantitative Results

The 66.20% of participants were women (n: 141) and 33.8% were men (n: 72). To the quantitative tools: 19.25% (n: 41) year 1 students; 20.19% (n: 43) year 2 students; 21.59% (n: 46) year 3 students; 12.20% (n: 26) year 4 students; 26.76% (n: 57) year 5 students were participated. Most of the participants lived with their family during pandemic (with family: 81.22%, n: 172; alone: 8.45%, n: 18; other options: 10.33%, n: 22). In addition, 80.75% (n: 172) of the participants stated that they experienced financial difficulties during the pandemic. The other descriptive statistics of the WSS scores in terms of variables in the student information form are given in Table 1.

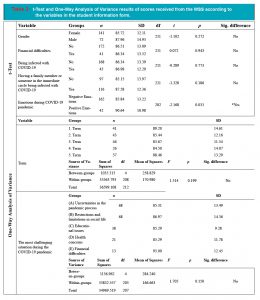

T-test analysis results for independent samples regarding the significant difference between the mean scores for gender, financial problems, the status of being infected with COVID-19, the status of having a family member or someone in the immediate circle being infected with COVID-19, and mood variables during the COVID-19 pandemic and One-Way Analysis of Variance results on the significant difference between the mean scores of well-being status regarding the most challenging situations during the COVID-19 pandemic are shown in Table 2.

According to the results of the analysis;

In terms of spiritual sub-dimension; a significant difference in favor of positive emotions was observed between the well-being spiritual score average of the students in the Negative Emotions group () and the well-being spiritual score average of the students in the Positive Emotions group () [t(204) = -2.117, p < 0.05], which showed that emotions had a significant effect on the spiritual sub-dimension of well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic period.

In terms of intellectual sub-dimension; a significant difference was found in favor of men between the well-being of female students’ intellectual point average () and male students’ well-being Intellectual point average () [t(209) = -2.068, p < 0.05], which suggested that gender had a significant effect on the Intellectual sub-dimension of well-being. Besides, a significant difference was determined in favor of positive emotions between the mean Intellectual well-being score of the students in the Negative Emotions group () and the mean intellectual well-being score of the students in the Positive Emotions group () [t(202) = -2.037, p< 0.05], which revealed that emotions had a significant effect on the Intellectual sub-dimension of well-being state during the COVID-19 pandemic period.

In terms of social sub-dimension; a significant difference in favor of positive emotions was found between the mean social score of the students in the Negative Emotions group () and the mean social score of the students in the Positive Emotions group () [t(80) = -2.214, p < 0.05], which showed that emotions have a significant effect on the social sub-dimension of well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic period. The mean scores of the WSS sub-dimensions were presented in Figure 2.

Qualitative Results

As a result of the analysis of the qualitative interview contents, the themes of emotions, learning process, well-being, difficulties and problems, achievements, coping methods, career planning, and suggestions emerged. The themes, sub-themes and related quotes are given in Table 3.

Discussion

Our research findings revealed that the pandemic has multi-layered effects on the daily lives of medical students. The Covid-19 pandemic has suddenly and rapidly changed the learning and teaching processes in medical education, and students have tended to question their developing professional competencies. The pandemic has had effects on students’ mental and social health as well as their physical health. These effects are discussed in this section under the headings of health status, psychological and social effects, learning processes, and career plans.

Health Status

Most of the students did not get infected with COVID-19 disease, most of them did not have a family member or close friend being infected with pandemic in our study. Despite this, the level of students’ anxiety about their health status was found to be high. Among their suggestions to their faculty administration, the demand to ensure the continuity of vaccination has come to the fore as the most important prevention regarding the pandemic. Most of the students lived with their families during pandemic.

Interest in physical well-being status is increasing day by day and is primarily supported by programs that promote healthy living behavior.(17) Students emphasized being healthy while describing well-being, in focus group interviews. Also, the students defined the health status as both not being sick and being in physical and mental integrity. These definitions are consistent with the definitions of the World Health Organization.(11) Although the benefits of physical activity to support well-being have been proven, people do not engage in physical activity at the recommended levels.(18) Students reported that their physical activity decreased in the first days of the pandemic.

Lack of physical activity arises from low motivation rather than inability to do physical activity.(19) In this context, maintaining physical well-being is related to other sub-dimensions of well-being. Healthy living behaviors were within coping strategies of students in pandemic. Students stated that they paid more attention to healthy nutrition and physical activity in pandemic. Health concerns were experienced more due to the ignorance/inadequacy of preventive and therapeutic health services in the early stages of the pandemic. However, it continued due to uncertainties after vaccination.

Among the suggestions of the students, there is no recommendation other than the vaccine for the protection of health. Therefore, it can be said that they are aware of the importance of the vaccination. It can be concluded that students manage their own health, and they do not have any expectations from their faculties in this regard.

Psychological and social effects

There has been an increase in the anxiety and depression levels of medical students during the pandemic.(20) Likewise, it was revealed that the students felt exhausted, anxious, nervous, and overwhelmed in our study. They defined individual-oriented strategies for coping with these negative emotions, and did not seek any psychological help to cope with these emotions. One of the coping strategies was expressed as increasing the time spent with family and friends. Family support has been defined by the students as a factor that strengthens the individual in coping with the stresses, in our study. In addition, self-awareness, realizing personal potentials, dedicating time for hobbies, taking responsibility in learning processes, and participating in online academic activities were revealed in our findings as other coping strategies.

It is thought that taking responsibility for their learning and getting different roles in daily life improves their psychological health. The students’ high self-control perception is associated with low anxiety and high academic achievement.(21) Therefore, the positive change in the self-control perceptions of the students included in our findings was evaluated as a protective factor. It was also revealed that involving in any social pro-jects protects psychological health. A person’s realization that s/he can be functional for the lives of other individuals, and that s/he experiences that s/he can create something meaningful for the benefit of another person is considered a healing factor in psychology under the title of the concept of altruism.(22)

A positive correlation between positive emotions and well-being was revealed in our study, and having positive emotions is positively related to the meaning of life, cognitive processes, and social relations. The pandemic has triggered students’ positive emotions, and they use personal resources to cope with negative emotions. It is a remarkable finding that the students in our study did not expect the school administration to do something (supporting psychological health) that would stimulate positive emotions.

This result is associated with the fact that a socially supportive climate in the learning environment is not prioritized in the institution. It is thought that providing support mechanisms (emotional support groups, wellbeing-centered mobile applications, etc.) that protect students’ psychological health and trigger their positive emotions are among the responsibilities of medical education institutions.(23) Such support mechanisms might be solutions to ensure the continuity of social interactions that have been interrupted by the pandemic or similar circumstances.

Learning processes and career plans

It was revealed that the distance education methods and restrictions imposed during the pandemic had various effects on students’ education in our study. Lectures were expressed as the most problematic aspects of online education by the students, and ‘lab lessons’ and ‘clinical setting courses (outpatient clinic, service visits, etc.)’ were the most significant areas that they thought to be improved. These results are similar with literature.(13-24)

Besides, implicit barriers to inter-institutional collaborations have disappeared, thanks to the use and development of distance learning systems, and gained momentum due to the pandemic.(24) In this way, the barriers to the online connection of students studying at one medical school to a course in another medical school can be reduced. Thus, inequalities of opportunity in medical education can be prevented. As emphasized by the students in our study, it is possible to improve institutional collaborations to overcome the inequalities in technical and academic opportunities.

In our study, the factors affecting the career planning were; the interruption of clinical education, being aware of their potential in non-medical fields. In addition, it is revealed that the problems of health professionals in health care services became more visible during the pandemic, which also effected their career plan. Despite the restrictions, the educational activities offered using simulation technologies and online interactive courses have positive contributions to the academic career planning of the students.(25)

During pandemic, students defined status of wellbeing in parallel areas with the WSS and stated that students’ education and career planning are important in maintaining their ‘intellectual well-being’ at the optimum level.(26) Students also suggested to policy-makers that it is uncertain how long the pandemic will last, therefore, if the sustainability of vaccination is ensured and necessary precautions are taken, online and face-to-face training should be carried out in a hybrid manner. In addition, they look forward to making observations in the clinical environment, taking part in the clinical environment, and being at the service of others again. Thus, by enabling students to observe their role models, and running on-the-job evaluation processes, students will be provided with a healthier career planning, and the “intellectual well-being”, will be supported. The main identified limitation of the study is that the 6th-term students could not be included in the study due to the intensity of the internship programs.

Conclusions

Healthy lifestyle behaviors are the first mentioned factors in coping strategies with the pandemic. Students defined the health concerns, which are among the difficulties encountered in the pandemic, as the ignorance/inadequacy of preventive and therapeutic health services, especially in the early stages of the pandemic, but continued due to uncertainties after vaccination. The pandemic has effected students’ career plans, and these were revealed that students tended to residencies with less risk, they wanted to avoid physical fatigue by getting away from the intense work tempo, and they wanted to maintain their health by working in areas where the risk of transmission is low.

Thus, by enabling students to observe their role models, and running on-the-job evaluation processes, students will be provided with a healthier career planning. Students reported that they felt exhausted, anxious, tense, and overwhelmed. They reported using individual-oriented strategies for coping with these negative emotions and did not seek any psychological help from the school to cope with these emotions.

They highlighted that medical faculties should offer solutions that center on social and emotional learning to ensure the continuity of social interactions that are interrupted in pandemic and similar situations. When the students’ opinions and the data obtained in the research were evaluated in terms of learning climate, the difficulties experienced in the presentations of lectures, the inability to perform basic medical practices, the decreased opportunity for reflection and social interaction emerged as significant findings. The reasons why students only used personal resources instead of asking for psychological health support from the faculty to cope with negative emotions can be revealed in the further studies. In addition, studies can be planned to design activities to support the well-being of students and reveal the possible effects of these activities.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research Ethics Committee. (Number: 2021/7, date: 24.02.2021). There is no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Consept: Selçuk Akturan (SA), Design: Selçuk Akturan, İnanç Sümbüloğlu (İS), Bilge Delibalta (BD), Gökhan Kumlu (GK) Supervision: SA, Data collection: SA, İS, BD, GK, Analysis: SA, İS, BD, GK, Literature Search: SA, İS, BD, GK, Writing: SA, İS, BD, References: SA, İS, BD, GK, Critical rewiew: SA, İS, BD, GK.

References

- McMahon S, Fleury J. Wellness in older adults: a concept analysis. Nursing Forum. 2012;47(1):39-51.

- Myers JE, Sweeney TJ, Witmer M. The wheel of wellness counseling for wellness: a holistic model for treatment planning. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2000;78(3):251–6.

- Korkut-Owen F, Owen DW. İyilik hali yıldızı modeli, uygulanması ve değerlendirilmesi [The well-star model of wellness, applications and evaluation]. Uluslararası Avrasya Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi. 2012;3(9):24–33.

- Renger RF, Midyett SJ, Mas FG, Erin TE, McDermott HM, Papenfuss RL, et al. Optimal living profile: an inventory to assess health and wellness. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2000;24(6):403-12.

- Korkut-Owen F, Doğan T, Demirbaş-Çelik N, Owen DW. İyilik hali yıldızı ölçeği’nin geliştirilmesi [Development of the well-star scale]. Journal of Human Sciences. 2016;13(3):5013-31.

- Dodge R, Daly A, Huyton J, Sanders L. The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing. 2012;2(3):222-35.

- World Health Organization [WHO]. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. 2021. Accessed from: https://covid19.who.int on 23 November 2021.

- Ghosh R, Dubey MJ, Chatterjee S, Dubey S. Impact of COVID-19 on children: special focus on the psychosocial aspect. Minerva Pediatrica. 2020;72(3):226-35.

- Martin A, Markhvida M, Hallegatte S, Walsh B. Socio-Economic impacts of COVID-19 on household consumption and poverty. Economics of Disasters and Climate Change. 2020;4:453-79.

- Mueller JT, McConnell K, Burow PB, Pofahl K, Merdjanoff AA, Farrell J. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on rural America. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2020;118(1):1-6.

- World Health Organization [WHO]. The social impact of COVID-19. 2020. Accessed from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/everyone-included-covid-19.html on 27 December 2020.

- Aker S, Mıdık Ö. The views of medical faculty students in Turkey concerning the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Community Health. 2020;45(4):684-8.

- Tokuç B, Varol G. Medical education in Turkey in time of COVID-19. Balkan Medical Journal. 2020;37(4):180-1.

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.1988.

- Morgan GA, Leech NL, Gloeckner GW, Barrett KC. SPSS for introductory statistics: use and interpretation. 2rd ed. New York, Psychology Press. 2004.

- Pituch KA, Stevens JP. Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. 6th ed. New York, Tyler & Francis Group. 2016.

- Rachele J, Washington T, Cockshaw W, Brymer E. Towards an operational understanding of wellness. Journal of Spirituality, Leadership and Management. 2013;7(1):3–12.

- Abdin S, Welch RK, Byron-Daniel J, Meyrick J. The effectiveness of physical activity interventions in improving well-being across office-based workplace settings: a systematic review. Public Health. 2018;160:70–6.

- Kaushal N, Bérubé B, Hagger MS, Bherer L. Investigating the role of self-control beliefs in predicting exercise behaviour: a longitudinal study. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2021;26(4):1155–75.

- Chandratre S. Medical students and COVID-19: challenges and supportive strategies. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development. 2020;7:1-2.

- Alemany-Arrebola I, Rojas-Ruiz G, Granda-Vera J, Mingorance-Estrada AC. Influence of COVID-19 on the perception of academic self-efficacy, state anxiety, and trait anxiety in college students. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11:1-7.

- Yalom I. Grup psikoterapisinin teori ve pratiği (The theory and practice of group psychotherapy). (translation eds) Karaçam Ö, Tanör A. İstanbul, Kabalcı Publisher. 2002.

- Deshetler L, Gangadhar M, Battepati D, Koffman E, Mukherjee R, Menon B. Learning on lockdown: a study on medical student wellness, coping mechanisms and motivation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Ed Publish. 2021;10(50):1-6.

- Ferrel MN, Ryan JJ. The impact of COVID-19 on medical education. Cureus. 2020;12(3):1-4.

- Reed B. Challenges to medical education on surgical services during the COVID-19 pandemic: a medical student’s perspective. Medical Science Educator. 2021;31(2):1.

- Cherak SJ, Rosgen BK, Geddes A, Makuk K, Sudershan S, Peplinksi C, Kassam A. Wellness in medical education: definition and five domains for wellness among medical learners during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Medical Education Online. 2021;26(1):1-4.