Kronik hastalığı olan ve olmayan çocukların psikososyal açıdan karşılaştırılması

Amaç: Tıptaki gelişmelere bağlı olarak kronik hastalığı olan çocuk sayısı artmıştır. Bu çalışmanın amacı, kronik hastalığı olan ve olmayan çocukların duygu durumları ve çevreleriyle olan ilişkileri açısından farklılık gösterip göstermediğini araştırmaktır.

Yöntemler: Bu olgu-kontrol çalışmasına pediatri polikliniklerine başvuran 4-11 yaş arası çocuklar dahil edildi. Herhangi bir kronik hastalığı olan çocuklar vaka grubuna dahil edilirken, tanımlanan herhangi bir kronik hastalığı olmayan, şikâyeti 10 günden az olan ya da şikâyeti olmayan çocuklar kontrol grubuna alındı. Çocukların bakım verenlerine demografik özelliklerle ilgili bir anket ile Güçler Yönler ve Güçlükler Anketi (SDQ) uygulandı. Sonuçlar SPSS 21 programı ile analiz edildi; betimleyici testler ve hipotez testleri uygulandı.

Bulgular: Hem olgu hem de kontrol grubu 125 çocuktan oluşuyordu; olgu grubundaki çocukların en uzun ikamet ettiği yerin kontrol grubundan istatistiksel açıdan anlamlı fark olarak ilçe ve/veya köy olduğu bulundu (p=0.011). SDQ ve alt grupları açısından olgu ve çalışma grupları arasındaki tek anlamlı fark duygusal zorluklardı (p=0,018). Karşılaşılan zorluklarla ilgili soruya verilen yanıtlar incelendiğinde, kronik hastalığı olan çocukların akran ilişkilerinde daha fazla sorun yaşadıkları (p=0.015) ve yaşam zorluklarının daha belirgin olduğu (p=0,038) görüldü.

Sonuç: Birinci basamakta çocuk hasta grubuna yaklaşımda, hastalığın potansiyel olarak çok yönlü etkileri akılda tutularak günlük yaşam olaylarının dikkatle ele alınması önemlidir.

Tam Metin

Introduction / Background

With advanced medical treatment methods, the number of children surviving with chronic disease has increased.(1,2,3) Having chronic disease (mucopolysaccharidosis, diabetes mellitus, etc.) increases risk of psychological status, the psychological evaluation of this condition could also be important for family physicians.(3,4) Although all innovations and techniques followed in medicine are followed by their respective specialties, the subject of psychological support is not given sufficient importance to patients and/or caregivers, whose role is very important in the treatment of the patient, and whose priority and importance, particularly the treatment of the patient, and whose priority and importance, particularly in developed countries, are indisputable.(3) The psychological state of the patient significantly affects the course of the disease. For pediatric patients, the importance of psychological support is indisputable.(5)

It is noteworthy that research specifically from the psychosocial perspective is insufficient. The recently accepted biopsychosocial approach emphasizes the importance of psychosocial evaluation in addition to medical treatment.(3) Therefore, comparing the psychosocial behavior of children aged 4-11 years with chro-nic disease to the behavior of those without can help to identify the effects of these diseases, and to realize the challenges caused. Any significant difference will emphasize that children with chronic disease are different from children without, and that approaches should be modified accordingly.

Aim

Chronic diseases require long-term treatment, and negatively affects quality of life. Especially in childhood and adolescence, individuals face many physiological and psychological changes. The additional burden of chronic disease may hinder their social and psycholoical development or cause various other problems.(6,7) In this research, the aim is to determine whether chronic disease affects the emotional state of children and their relationships with the environment. The ethical permission of the study was approved by the ethical committee of Dokuz Eylul University (DEU: 2013 / 13-14 11.04.2013).

Method

Descriptive case-control study.

Population and sampling: The population of the study was 4-11 years old children selected from among the outpatient and inpatient patients admitted to DEU, Child Health and Diseases Department. Children with chronic disease were compared with children without (between January and June of 2014). The sample size was calculated to be at least 111 children for each group with 80% power, 95 % CI, OR:3 and prevalence of 10%. The cases were selected consecutively among the patients who were hospitalized in the pediatric ward and followed up at the subspeciality clinics.

The control group, on the other hand, were the children who applied to the general and “well-child” outpatient clinic of pediatrics, either with no complaints, or with complaints of durations of less than 10 days, and who were identified in the research as not having chronic diseases. Children included in the control group were matched in terms of age and gender. “Having chronic diseases” is defined as either diseases that have existed longer than 3 months or have a high probability of continuing more than 3 months. Also, diseases having clinical symptoms 3 or more times a year were considered as chronic diseases. Seven disease groups were included according to this definition.(8,9)

- Chronic Respiratory Diseases (Asthma)

- Congenital heart diseases

- Hematological-oncological malignancy

- Metabolic diseases (Diabetes)

- Neurometabolic disease

- Chronic kidney failure

- Rheumatologic diseases (Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis)

Child volunteers between the ages of 4-11 participated in the study. Those with any psychological issues were not included in the study.

Data Collection Tools:

– Sociodemographic data form

– Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire – SDQ: This tool was developed by Robert Godman and has been translated into different languages. This questionnaire includes the parent form and school form for ages 4-16, and the adolescent form for 11-16 ages. The adolescent form contains the same items as the parent form, except that for many items, the first-person singular pronoun is used instead of the third person. It contains 25 questions, which focus on either positive or negative behavior characteristics. These questions are presented in five categories: behavioral problems, attention deficit and excessive mobility, emotional problems, peer problems, social behaviors.

As each category is evaluated alone, the sum of the first four categories gives the ‘total difficulty score’.(10) The Turkish validity and reliability of the questionnaire was performed by Güvenir et al. (Cronbach alpha values were: emotional 0.70; behavioral problems 0.50; attention deficit and excessive mobility 0.70; peer problems 0.22; social behavior 0.54; and for the total difficulty score 0.73).(11)

Results

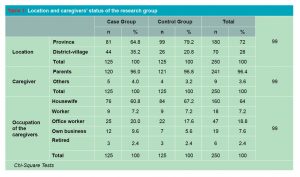

125 children were included in each group; and no differences were observed between the two groups regarding age, gender, and their caregivers. The longest place of residence for children in the case group was found to be a town or a village, which was statistically different than the control group (p=0.011 Table 1).

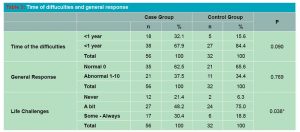

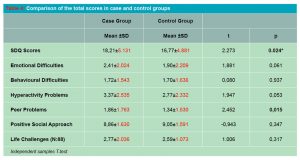

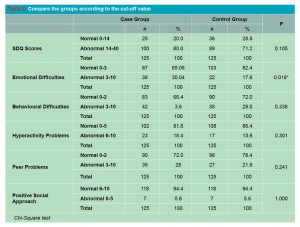

Regarding SDQ and its sub-groups, there were no significant differences between the case and study groups. Additionally, there was no significant relationship between the duration of the disease and the ratings (Table 2).

When asked about difficulties in their lives on a Likert scale: “never, a little, some and always”, 88 participants answered (56 participants with chronic disease, 32 participants from the control group). Table 3 and Table 4 givethe results of these 88 participants.

Discussion

In our study, it was observed that children with chronic diseases were psychosocially no different from their peers according to the total scores they got from the SDQ. Rothenberger et al reported that SDQ is appropriate for screening but there is not sufficient evidence for multicultural setting.(12) Richter et all revealed that SDQ may produce different results among ethnic Norwegian samples, although this tool is “internationally most frequently used screening instruments for child and adolescent mental health purposes”.

We did not collect information about cultural and ethnic diversity of the children included to study. The subscale scores are considered more valuable than the total.(13) When we used the cut-off scores to evaluate subscales, only emotional difficulties were significantly different between the groups.(12) When children begin to attend kindergarten or elementary school, they do not gain knowledge but also the social norms and values of their communities.(14) Emotional difficulties may hinder integration with peers in the case group.

When the responses to the question concerning difficulties / challenges faced were assessed, it was discovered that children with chronic conditions had more/greater difficulty with peer relationships. The SDQ is a self-assessment tool, and children with chronic diseases reported having difficulty with peer relationships. Many research have led to similar findings, demonstrating that peer relationships are indeed an issue.(15,16) The impact of peer relationship can be used to encourage healthy lifestyles, education, as well as other interests, although it varies depending on the individuals. (15,17)

Socioeconomic disadvantage negatively affects every dimension of child development, including mental health and well-being.(18,19) In our study, most children with chronic disease lived in small towns and/or villages. While some studies reported that low socioeconomic status was associated with greater emotional and behavioral problems, this result was not revealed in our study.(12,18)

Academic success and satisfaction in adult life are key problems to address for the children with chronic diseases.(16) Life challenges were more significant in the children with chronic disease group in our study. A holistic approach towards family medicine could be a key solution during the follow-up of these children. (20,21,22) In the approach to the pediatric patient group in primary care, daily life issues should be carefully considered, and it is important to remember that the effects of the disease may be multifaceted. “Life challenges” is a problem not only for healthcare workers but also for policymakers. Children with chronic disease may be anxious about their future lives. However, social networks, societies, and stakeholders all have responsibility for the future of these children. Lack of probing the effect of cultural diversity may be considered as the limitation of this study.

Conclusion

Children with chronic illnesses should be supported to achieve healthy mental development not only in extraordinary times such as COVID-19 Pandemic but also in daily practice. Healthcare workers can manage this issue just to work as a team due to monitor the follow-up chronic care and produce solutions for problems that do not attract attention at first glance, especially “peer problems” which could be normalized. The issue that most of the children with chronic diseases were located in rural areas should be investigated. Community-oriented primary care could be considered as an option to solve the vulnerable social conditions.

Referanslar

- Chakravorty S, Williams TN. Sickle cell disease: A neglected chronic disease of increasing global health importance. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100: 48–53.

- Care D, Suppl SS. Children and adolescents: Standards of medical care in diabetes- 2020. Diabetes Care 2020; 43:163-82.

- Karakök B. Ankara ve İstanbul’daki HIV/AIDS Merkezlerinde takipli HIV (+) olan çocuk ve ergenlerin ruh sağlığı ve bilişsel fonksiyonları açısından incelenmesi ve orta-ağır şiddetli astımlı çocuklarla karşılaştırılması. Uzmanlık Tezi. Ankara, Hacettepe Üniversitesi, 2017.

- Kuratsubo I. et al. Psychological status of patients with mucopolysaccharidosis type II and their parents. Pediatr Int 2009; 51:41-7.

- Vugteveen J, de Bildt A, Hartman CA, Reijneveld S, Timmerman ME. The combined self-and parent-rated SDQ score profile predicts care use and psychiatric diagnoses. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2021; 30:1983-94.

- Selewski DT, et al. The impact of disease duration on quality of life in children with nephrotic syndrome: a Midwest Pediatric Nephrology Consortium study. Pediatr Nephrol 2015: 51: 1467-76.

- Kaya Ç. et al. Kronik hastalık bakımının hasta perspektifinden değerlendirilmesi. Turkish Fam Physician 2013;4: 1-9.

- Torpy JM, Lynm C, Glass RM. Chronic diseases of children. Jama 2007; 297: 2836.

- Mokkink LB, Van Der Lee JH, Grootenhuis MA, Offringa M, Heymans HSA. Defining chronic diseases and health conditions in childhood (0-18 years of age): National consensus in the Netherlands. Eur J Pediatr 2008;167:1441-7.

- Goodman R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip 1997;38:581-6.

- Güvenir T. et al. Güçler ve Güçlükler Anketinin (Gga) Türkçe uyarlamasının psikometrik özellikleri. Çocuk ve Gençlik Ruh Sağlığı Derg 2008; 15: 65-74.

- Rothenberger A, Becker A, Erhart M, Wille N, Ravens-Sieberer U. Psychometric properties of the parent strengths and difficulties questionnaire in the general population of German children and adolescents: Results of the BELLA study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008; 17: 99-105.

- Richter J, Sagatun Å, Heyerdahl S, Oppedal B, Røysamb E. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) – Self-Report. An analysis of its structure in a multiethnic urban adolescent sample. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip 2011;52:1002-11.

- Van Lier PAC, Koot HM. Developmental cascades of peer relations and symptoms of externalizing and internalizing problems from kindergarten to fourth-grade elementary school. Dev Psychopathol 2010; 22: 569-82.

- Hay DF, Payne A, Chadwick A. Peer relations in childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip 2004; 45: 84-108.

- Taras H, Potts-Datema W. Chronic health conditions and student performance at school. J Sch Health 2005; 75: 255-6.

- La Greca AM, Bearman KJ, Moore H. Peer relations of youth with pediatric conditions and health risks: Promoting social support and healthy lifestyles. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2002; 23:271-80.

- Bøe T, et al. Socioeconomic status and child mental health: The role of parental emotional well-being and parenting practices. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2014; 42:7-15.

- Peters I, Handley T, Oakley K, Perkins D. Social determinants of psychological wellness for children and adolescents in rural NSW. BMC Public Health 2019; 19: 1-11.

- Utlu Y, Başak O. Uzmanlık eğitimini yeni bitirmiş aile hekimliği uzmanlarının yeni çalışma dönemlerine bakışları ve birinci basamak aile hekimliği uygulamasından beklentileri. Jour Turk Fam Phy 2018; 9: 98-103.

- Özkul SA, et al. İstanbul’da Aile Sağlığı Merkezlerinde koruyucu adolesan sağlığı yaklaşımında kaçırılmış fırsatlar. Turk Fam Phy 2015; 6: 18-9.

- Baska A, Kurpas D, Kenkre J, Vidal-Alaball J, Petrazzuoli F, Dolan M, et al. (2021). Social prescribing and lifestyle medicine—a remedy to chronic health problems? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(19):10096.